On the Eve of the Pilotage Corporations

In 1833, the pilots considered it essential to create an organization outside of the Montreal Trinity House in order to ensure the sound management of marine pilotage. They mandated Notary Louis Panet to draft a legal text, the foundation document of the Society for the “Branch Pilots for and above the Harbour of Quebec”. Naturally, this initiative does not please Trinity House, which holds administrative authority. This action ended in failure. In fact, the application for the creation of an official entity external to the Trinity House to regroup the pilots is rejected. They are denied this right.

But pilots never throw in the towel! On May 21, 1850, they addressed a petition to the House of Assembly of Lower Canada demanding the creation of a corporation, but this time under the dome of the Trinity House of Montreal. After being scrutinized by the latter, the request was carried by the deputy of Portneuf, Antoine Ch. J. Duchesnay. After several amendments requested by the Board of Trade and Trinity House, the Act to incorporate the Pilots for the Quebec harbour and above was signed on August 10, 1850.

The Corporation of Pilots for the Quebec City Harbour and Above Is Born!

The Corporation of Pilots for the Quebec City Harbour and above became reality! The Corporation was a public group to which belonged the pilots practising upstream of the Quebec harbour. It had obtained “the right to exercise regulatory, disciplinary, arbitral, and administrative functions… Finally, it exercised various powers not in the interest of a particular individual or group of individuals, but of the profession and of society as a whole.” (Pierre Harvey, “L’organisation corporative de la province de Québec” (corporate organization of the province of Quebec), L’Actualité économique, April 1953)

The Tour de Rôle Association

However, although pilots were now members of a corporation, there was still a point of contention among them: the manner of assigning pilots to the vessels. Within the corporation, there were pilots of the tour de rôle (by rotation) type and pilots who were hired directly by the shipping companies and assigned only to their ships (free competition). This sometimes led to stormy relations because of diverging interests. Moreover, in addition to maintaining a climate of competition, this situation left a certain disorganized pilotage and availability of pilots. In 1870, the idea emerged to create an association whose guiding principle would be to assign pilots by rotation and no longer be subjected to a mode of operation based on free competition. It was in Deschambault, in the spring of 1873, that the official documents of the Association du tour de rôle were signed.

It is easy to assume that discussions were agitated between the supporters of the “rotation” system and those who wanted to keep their privileges as competing pilots. However, a compromise was reached and a first committee of five elected pilots was created based on this compromise.

But even though this committee was completely legitimate, it was not easily accepted. In fact, Port authorities had doubts concerning the competence of the pilots to manage a corporation. What’s more, in 1873, the Commission du Havre de Montréal still did not recognize the Pilots’ Committee. It was therefore difficult to make their voices heard.

A Stormy Patch…

The following years were marked by various demands, which remained unanswered. Exasperated by this indifference, the Association du tour de rôle warned that it wished to form a corporation, distinct from that of the Pilots for and above the harbour of Quebec. This stirred up the authorities and seems to break the deadlock … but only in theory. No concrete changes were made.

Then, in 1884, a request for incorporation was submitted to Parliament. But it failed because of the shipowners’ and port authorities’ objections. In 1896, a second attempt again led to disappointment. That year was particularly stormy between pilots and shipowners who also considered that the pilots were incapable of managing a corporation and the pilotage organization.

Tired and irritated with the contempt they were facing, the members of the Quebec City to Montreal Pilots Association, led by Cléophas Auger, voted for a mandate to strike. As a result, on June 18, 1897, the 52 pilots working in the district between Quebec City and Montreal stopped all work until the 26th of the same month. During this period, it was impossible for ships to use pilotage services at the Port of Montreal to sail down the St. Lawrence. In addition, the “upper” pilots who had remained in Quebec City after their last mission were also out on strike. Thus, no pilots boarded ships bound for Montreal. By December 31, 1897, although the strike had been over for several months, the conflict had not yet been resolved.

The conflict was resolved by a commission of inquiry chaired by Judge John Lavergne and commissioned by the Minister of the Navy in January 1898. Among the issues being examined were the relationship between pilots, shipowners, import/export merchants, and the pilotage authority, the number of licensed and active pilots, the training of apprentices, and maintenance of the navigation channel and its buoyage.

Public hearings were held. It was at this time that Cléophas Auger submitted his Mémoire des pilotes (pilots’ brief), in which he made several recommendations. Finally, the Commission of Inquiry took into account the comments made during the hearings and paid particular attention to the brief regarding pilot training and the maintenance of the navigation channel.

At the same time, the Ministry of the Navy and Fisheries became more prominent. Under Bill 261, the responsibility for pilotage between Quebec City and Montreal was entrusted to this government body and thus withdrawn from the Montreal Harbour Commission, which was dissolved in 1903.

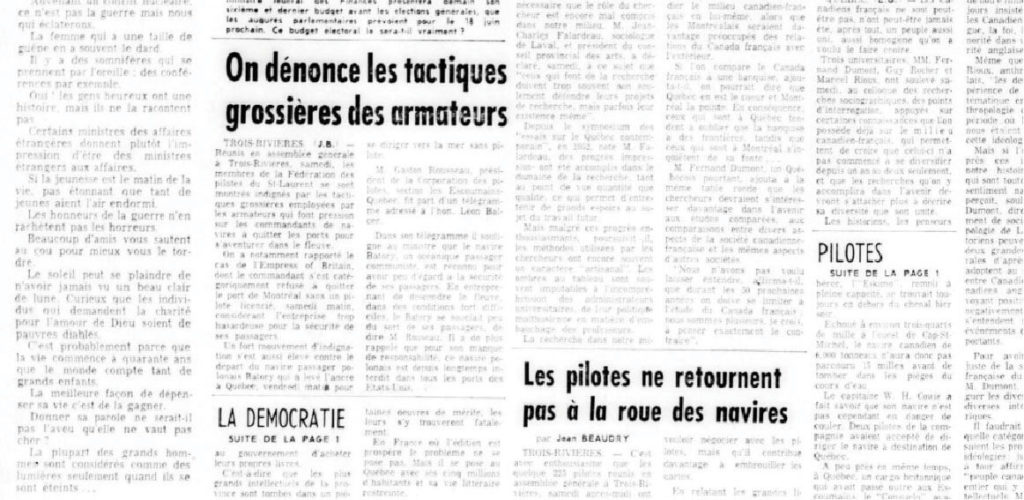

When the strike began in June 1897, several newspapers reported the story. Just like La Presse, the newspaper La Patrie published a first article on the subject on June 19.

Source BAnQ :

“Très grave complication provoquée par le rejet du bill des pilotes au Sénat” (very serious complication caused by the rejection of the pilots’ bill in the Senate), La Patrie, June 19, 1897.

“La grève des pilotes” (the pilots’ strike), La Presse, June 24, 1897.

The Corporation des Pilotes du Saint-Laurent Central Sets Sail

United Pilots Association of Quebec in Montreal

Despite the era of change pilots had gone through, much remained to be done. The demands were voiced, but difficult to win. In order to increase their bargaining power, the pilots founded the United Montreal Pilots Association in Deschambault on December 27, 1918. In all, 33 pilots made up this professional association.

Other changes in the operation of the profession were made, such as pooling pilots’ income. Also, the term of the work contracts between the pilots and the United Pilots Association of Quebec in Montreal was extended to 25 years.

The Corporation des Pilotes du Saint-Laurent Central

In 1958, a new organization was created, the Corporation des pilotes du Saint-Laurent central (CPSLC). It operated alongside the Association des Pilotes Unis de Québec in Montreal until 1968, at which time the CPSLC replaced it.

Today, 122 pilots work with the CPSLC to ensure the safety of ships in the sector between Quebec City and Montreal.

Since the creation of the Association du tour de rôle in 1873, over 600 pilots have served on behalf of the current CPSLC. This means thousands of pilotage missions, millions of tonnes of cargo, and crews from all over the world!

Once a pilot has boarded a vessel, tradition and rules in certain countries dictate that the crew must hoist the HOTEL flag of the International Code of Signals. This visual mark signifying that there is a pilot on board is no longer mandatory in Canada, but most vessels transiting our waters still follow this tradition.

Pilots From Generation to Generation

At the time, the profession of marine pilot was one that often spanned generations. Thus, family lineages of pilots such as the Bouillé, the Perreault, the Paquet, the Naud, the Bélisle, the Gauthier, the Raymond, the De Villers, the De Lachevrotière, and the Arcand lived on the shores of the St. Lawrence. Many pilots in the area between Quebec City and Montreal are from Deschambault and Lotbinière. Pilots usually earn their pilot’s certificate in their early thirties.

A River and Its Challenges

“Discipline conquers all obstacles.”

– Leonardo da Vinci –

The section of the river covered by the CPSLC pilots extends from the Port of Quebec to just west of the Port of Montreal. This is a very large stretch of river, covering a distance of 135 nautical miles (243 km)! Because this is a very long route to be navigated by a single pilot, this area has been divided into two sectors since 1959 (to which the sector of the Port of Montreal will be added):

1. Quebec—Trois-Rivières

2. Trois-Rivières – Montreal

The group of pilots is equally divided between the two sectors.

Interesting Fact!

Recall that the pilot is a specialist in the sector to which he is assigned. Pilots hold a certificate that is valid only within one of the two sectors or within the limits of the Port of Montreal. Therefore, they perfectly master the knowledge and the risks related to it. A necessity? Absolutely!

Responsibility for the intermediate ports is also well distributed: those for pilotage at the ports of Bécancour and Trois-Rivières are assigned to the pilots of the Quebec City—Trois-Rivières sector. While those at the ports of Sorel and Contrecœur are assigned to the pilots of the Montreal–Trois-Rivières sector. The Port of Trois-Rivières, which is adjacent to both sectors, is shared between the pilots of both sectors.

Bulk carrier in the Quebec area

Photography : André Lavoie

Only One Type of Marine Pilotage? No!

In the area between Quebec City and Montreal, there are two types of pilotage: manoeuvring and river pilotage.

Manoeuvring generally consists in arrival or departure from one of the many docks in the ports of Quebec, Trois-Rivières, Montreal, or one of the intermediate ports (Sorel, Bécancour, Contrecœur, etc.). Manoeuvring can be performed with or without the assistance of harbour tugs, depending on the type of wharf, the vessel’s characteristics, the weather, and the current.

River pilotage involves conducting the vessel while it is underway in the navigation channel, 24/7, 365 days a year.

Vigilance Is Critical

There are many issues related to navigation in this area: shallow water in the channel, poor visibility caused by rain, fog, snow and sea smoke, heavy traffic, and ice. In addition, the waterway is winding and narrow, which adds an element of risk. Between Montreal and Quebec City, the channel is 245 metres wide and 11.3 metres deep. Downstream, between Quebec City and Trois-Rivières, this depth is only 10.7 metres. Caution is not an option, but a duty!

What Does a Pilotage Mission Look Like?

A marine pilot’s workday begins long before he or she is standing in the wheelhouse. Preparation is necessary in order to have some data in hand before boarding and exchanging information with the captain. Let’s take a look at what a pilot’s work day might look like when he embarks in Quebec City to pilot a ship to the Port of Trois-Rivières…

1. Four hours before the ship arrives at the pilot station, a pilot is assigned to the ship by the Laurentian Pilotage Authority.

2. The pilot examines the water levels in the river, the weather forecast, and the technical characteristics of the vessel. He also reviews the expected vessel traffic during its transit.

3. He arrives at the pilot station about thirty minutes before the ship arrives. He then boards the pilot boat to join the ship, which is underway.

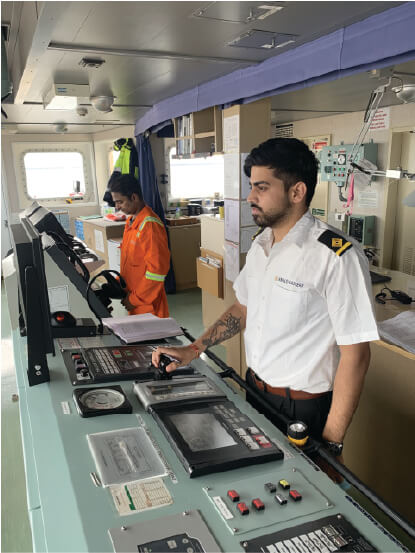

4. The pilot is greeted on the bridge by an officer and immediately goes to the wheelhouse since this is where piloting is carried out.

5. The pilot and the master discuss the characteristics of the vessel, the weather conditions, and the equipment on board in order to plan the transit.

6. The pilot immediately takes charge of the ship, transmitting the course to the helmsman and the speed to the officer in charge of the telegraph. There is no time to lose, because the ship is still moving on the river!

Although the master is usually present at the beginning or end of a transit, the pilot works more closely with the navigation officer, the master’s representative, and the helmsman.

7. At the end of the transit, the pilot conducts the manoeuvre at the dock in the Port of Trois-Rivières.

If the dock assigned to the vessel is not free, or when the vessel must remain on standby, the vessel must proceed to various anchorage areas: Saint-Nicolas, Trois-Rivières, Sorel or Lanoraie.

8. When the berthing or anchoring manoeuvre is completed, the pilot leaves the ship.

Following a mission, the pilot must be off duty for a minimum period of 10 hours before being assigned to another vessel. Furthermore, the work period-the pilot’s rotation is approximately two weeks per month. During this period, he must be available 24/7 and he will pilot about ten vessels. He will then be off duty for two weeks before going back on rotation.

Interesting Fact!

A transit between Quebec City and Trois-Rivières takes approximately 6 hours. In the opposite direction, it takes approximately 4 hours and 30 minutes. The same is true for a transit between Trois-Rivières and Montreal.

Pilot Transfers… Not Always Easy!

What is the essential device used by the pilot when he boards the ship to be conducted? A ladder … made of rope!

As the pilot boards the vessel, it has to slow down, but it still continues its course on the river. To enable the pilot to board the vessel, the bridge team slides a ladder along the hull. Meanwhile, the pilot boat must remain as stable as possible while the pilot grabs the ladder and puts both feet on it. Depending on the weather conditions, it is easy to imagine that this operation can be quite dangerous! Pilots are required to wear a life jacket during this operation.

Construction of a pilot ladder and the method used by the crew for docking must comply with strict rules dictated by the IMO’s (International Maritime Organization) SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) Convention.

And What Tools Are Used to Pilot a Ship?

Navigation on the river was not always carried out with the help of a GPS! Over time, navigation tools and piloting techniques have evolved at the same pace as the new available technologies. Since the 1970s, technology has increasingly been used on board ships.

For example, between 1960 and 1980, more efficient and accurate navigational radars were introduced into wheelhouses. When darkness or poor visibility prevails, radar navigation becomes essential. This electronic instrument allows the pilot to carry out precise navigation using distance measurements taken on the screen of the instrument.

In the 1990s, in addition to visual piloting and radar techniques, a tool was added to validate positions: the electronic chart on which the GPS position of the vessel is observed. Satellite positioning systems (GPS) are being added to the pilots’ toolbox, allowing them to maximize the size of vessels on the river.

With these new technologies, does the pilot still need charts? Yes! Some tools will always be needed, and charts are one of them. Pilots use electronic charts produced by the Canadian Hydrographic Service. The Canadian Hydrographic Service has been studying Canadian waters since 1883 to ensure their safe and sustainable use.

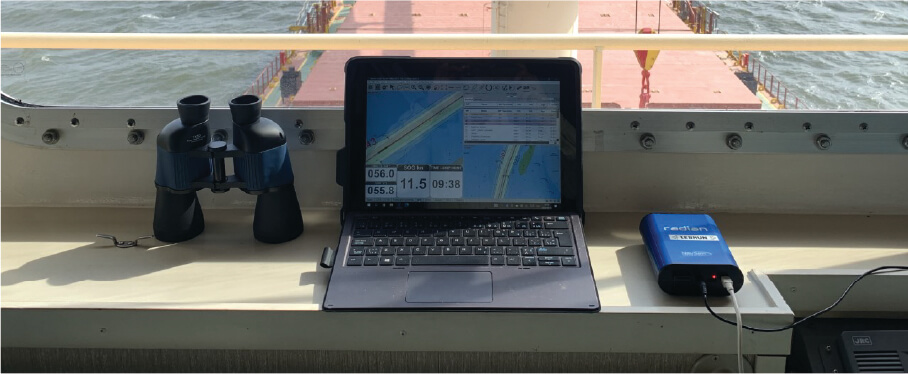

Since 2008, the Portable Pilot Unit (PPU) has also become an essential tool on board vessels. In fact, each pilot has his own PPU that he uses for each of his missions. It is a laptop computer on which is installed an independent electronic navigation system that has its own positioning mode, but is also connected to the ship in order to receive a maximum of information in real time.

In 2008, an electronic information system—to which the PPU is connected—was implemented and allows for increased safety for the transit to Montreal. Among other things, it allows pilots to have access in real time to a host of information necessary for navigation on the river: channel conditions, shoals, ice cover movements, water levels, tides, navigation notices, etc. Also, thanks to the AIS (Automatic Identification System), pilots know the position of other vessels in their navigation sector at all times.

What Is the Laurentian Pilotage Authority?

This public body, under federal jurisdiction, is responsible for managing and providing marine pilotage and related services in the waters of the Laurentian region, particularly in the St. Lawrence and Saguenay River sectors. In order to ensure safe navigation, its mission is to manage an efficient marine pilotage service in collaboration with pilot corporations and the marine industry.

Navigating “By Sight”

Since the early days of marine pilotage, pilots have developed a precise navigation technique that relies strictly on visual sea marks. Even today, despite all the technology on board ships, this technique is still used.

What is a sea mark? They are physical points of reference located on land and on the river. Some are visible day and night (buoys, lighthouses, range lights, electrical towers) while others are only visible by day (mountains, church steeples, specific buildings). By using these sea marks, pilots know where the vessel is in relation to the centre of the channel, while other visual points of reference indicate when they need to change course.

These visual markers are essential when changing course and all pilots must be very familiar with them. For example, between Quebec City and Montreal, there are approximately 200 course changes, which involves many of these visual markers and an excellent memory of them.

Here, the Federal Champlain in the Trois-Rivières sector.

Source: Gary Waters

A Constantly Evolving Profession

The history behind the profession is not exactly a smooth and easy one! There have been many challenges along the way, but they were all necessary. In the midst of change, progress and new perspectives have been observed. In a continuously evolving world such as shipping and maritime commerce, new ways of thinking are imperative. As in the late 18th century, changes in recent decades have created a re-examination of how things are done. Each era has its own turmoil!

1962–1971 Royal Commission

In 1962, navigation on the river was becoming increasingly important. The number of ships from all over the world was increasing, and with it, maritime traffic. Faced with this increase, the pilots, who were subject to a 30 consecutive day, 24-hour work schedule, are struggling to keep up with demand. They are calling for additional staff to be hired. However, the federal government, which regulates hiring, considers that the number of pilots is adequate and denies the request. At this point, the pilots declared that they would not board another ship until the government changed its mind.

The government was faced with a dilemma, as the seaway was opening and ships in transit were flocking onto the river, raising concerns about maritime safety. Faced with the pilots’ strike, the government threatens special legislation. However, if the pilots returned to work, a Royal Commission on pilotage would be initiated to validate or invalidate the requests and make the necessary changes. The pilots agreed. But what was supposed to be an investigation of the district between Quebec City and Montreal was extended to all of Canada. Consequently, the delays were longer. The inquiry ended 9 years later in 1971 and included 39 recommendations. The Report of the Royal Commission on pilotage, chaired by the Honourable Justice Yves Bernier, gave rise to the Pilotage Act, an integral part (section 6) of the Canada Shipping Act.

When the strike began in 1962, the pilots’ demands were not limited to the number of employees. Working conditions were the most important issue on the list of demands.

1. Recognizing the Skills and Work of Pilots

Before 1971, masters and shipowners viewed pilots as mere technical advisors. They were not responsible for the conduct of the vessel and acted in an “advisory” capacity. Their presence, in the wheelhouse and on the bridge, did not mean that their recommendations would be accepted, as this was at the master’s discretion.

In 1971, the Pilotage Act changed the pilot’s status from technical advisor to responsible for navigation in Canadian waters. A major change within the profession.

2. Income

Pilots wanted to see pilotage tariffs increased while the Canadian Shipowners’ Association wanted to maintain the status quo. Negotiations are often necessary to settle this part of the dispute.

3. Remuneration of Apprentice Pilots

In the past, aspiring pilots did not receive any remuneration for their pilotage missions as this remuneration was refused by shipowners. However, it is in the shipowners’ interest to ensure that they receive adequate training and that they are remunerated commensurate with their efforts. After all, these apprentices are the ones who will safely operate their ships in a few years.

4. Availability of Pilots

Being a pilot means you must be ready to board a ship at any time of the day or night with very little notice. And yet, pilots are aware that a pilotage mission requires meticulous preparation. In 1980, a regulation was passed requiring that a pilot be given 4 hours notice when being assigned a pilotage mission.

In 1974, although it had been 3 years since the Royal Inquiry, there was little concrete change. After many demands, pilots went on strike, under the threat of special legislation from the federal government. To resolve the conflict, it was decided to opt for an arbitration system.

The pilots’ demands were finally accepted in 1975, 13 years after the 1962 Royal Commission on Pilotage began.

The Pilotage Act of 1972, as Revised

In May 2017, Transport Canada launched a review of the Pilotage Act to modernize it. One year later, a final report was submitted with 38 recommendations. These include revising the objectives of the act itself, improving the pilotage governance model, revising the risk analysis methodology and streamlining the process for setting tariffs.

April 6, 1962

The pilots’ strike paralyzed maritime traffic on the river. At the negotiation table, the representatives of the St. Lawrence pilots and the Shipowners’ Association. At the centre of discussions: wage increases and improved working conditions. Several ships were immobilized, including cruise ships with hundreds of passengers on board.

Women in Pilotage

Still today, women are rare in the world of piloting. There are an estimated 6 women pilots in Canada out of a total of 440. Interestingly, they all navigate on the St. Lawrence River: 4 between Les Escoumins and Montreal and 2 on the seaway leading to the Great Lakes. Nevertheless, an increase in the number of women is becoming apparent. For instance, in the last few years, an increase in enrolment has been noticed in the Navigation and Transportation Logistics Techniques programs at the Institut maritime de Rimouski. This trend is good news: it ensures a succession, in addition to bringing diversity to the teams.

Traditionally a male profession, there is now more room for women in this field and the door is wide open for them in the job market. Moreover, the more female role models there are in the maritime professions, the more women will be interested and want to pursue a career in this field.

Captains’ Curiosity

Despite the fact that they are on board for many hours, pilots never leave their post. There are no breaks. How do they eat, for instance? Meals are brought to them, which they will eat in the wheelhouse. Interestingly, sometimes pilots have to eat in the dark since all the lights are turned off at night to preserve better night vision!